Structured expert elicitation for long-term survival outcomes in health technology assessment: a systematic review | BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making

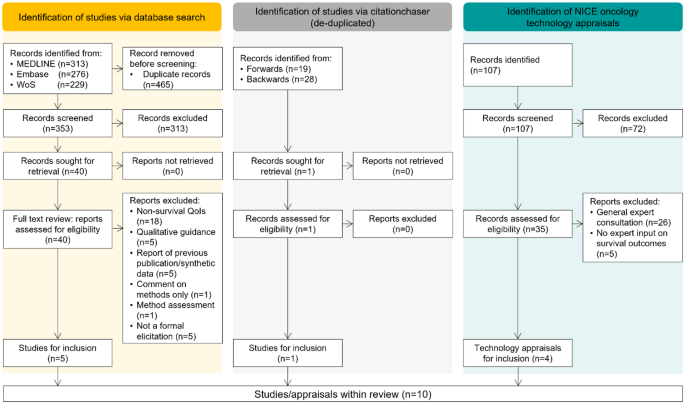

Bibliographic database searches retrieved 353 unique articles, of which 313 articles were excluded based on the assessment of non-relevance during title and abstract screening. Searching of the NICE published guidance database identified 107 technology appraisals, of which 72 were not related to oncology or were terminated appraisals. Of the 40 studies and 35 appraisals subject to a full-text review, including those identified from the forward or backward pearl-growing, 6 studies and 4 recent technology appraisals had used structured expert elicitation for long-term survival outcomes, (Fig. 1, see supplementary material for list of included studies and appraisals).

Of the studies identified within the broader literature, all studies were published between 2019 and 2023. Five out of six of the studies were within oncology [7, 8, 21, 26, 27], with the sixth study based in renal disorders [23]. The four NICE technology appraisals (TA), henceforth referred to as ‘appraisals’: TA917 [28], TA954 [29], TA967 [30], and TA975 [31], related to multiple myeloma, B-cell lymphoma, classical Hodgkin lymphoma, and lymphoblastic leukaemia respectively. The four appraisals were all submitted by different companies and received positive guidance for the proposed interventions. Whereas in the six studies identified within the broader literature, two of the studies, authored by Ayers et al. and Cope et al., had significant overlap in contributing authors [7, 8].

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) diagram of broader literature search and targeted review of recent NICE oncology appraisals. QoI, quantity of interest

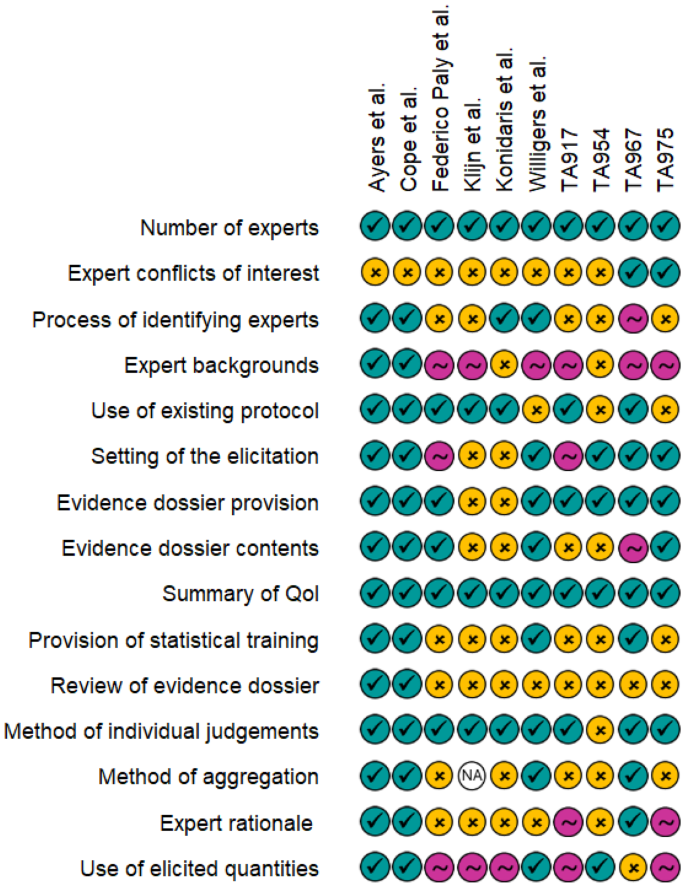

Reporting quality of studies/appraisals

For each of the included studies and appraisals, reporting detail of common elements of elicitation exercises was assessed. These were graded as: completely reported; partially reported; or not reported (Fig. 2). It is evident that some items, such as the number of experts or the definition or the quantity of interest are generally well reported, but other items such as expert declarations of conflicts of interest or the process of identifying experts are more variably reported. Expert backgrounds tended to be introduced within the studies, but then not expanded on. The eventual use of the elicited quantities was not always discussed fully within the studies.

Reporting quality assessment of included studies and appraisals. Teal ticks indicate complete reporting, pink tilde indicates that the item was mentioned but additional details are required for full understanding of the process, and yellow crosses indicate that the item was not reported. TA, technology appraisal; QoI, quantity of interest

Selection and identification of experts

Studies identified from the broader literature had between one [26] and nine [27] experts, with a median of six experts. These experts were involved in all stages of the elicitation, whereas in the NICE appraisals there were between three [31] and ten [28] clinical experts with variable contributions within the elicitations. For instance in TA975, despite the recruitment of six clinical experts, only five were able to provide their individual judgements due to technical issues, but all experts contributed within the discussions [31].

Expert declarations of conflicts of interest were not included within any of the studies identified from the broader literature, and this was similarly not discussed extensively within the appraisals. Only TA967 and TA975 stated that this information was collected but it was not presented within the publicly available documents [30, 31]. However, this information may have been available for the NICE committee and external assessment group during review of the submission via the supporting appendices. Alternatively, conflicts of interest could have been included as part of the expert selection criteria, with only those without conflicts deemed eligible; however, it is unclear whether this was the case. Throughout this review, it is noted that the assessment of the appraisals is limited to the publicly available information and documents, however references to supporting documents (which are not publicly available) is highlighted.

The process of selecting experts was variably reported. Ayers et al. and Cope et al. described the process of selecting experts, largely with a focus on “criteria” for the expertise of participating experts as well as expert experience with the intervention(s) [7, 8]. The study by Konidaris et al., associated with NICE TA592, did not include explicit description of the expert selection process but within Document B of the associated appraisal, it was highlighted that all experts were required to have treatment experience with the intervention and were recruited from the pool of trial investigators [27, 32]. Federico Paly et al., Klijn et al. and Willigers et al. did not include significant information regarding the selection process of the experts [21, 23, 26]. No details of the expert selection process, or attempts to ensure panel diversity were discussed in any of the four NICE appraisals.

The discussion of expert backgrounds or expertise was largely correlated with the level of detail on the expert selection process. Both Ayers et al. and Cope et al. provided detailed, quantitative descriptions of experts, including: proportions of time spent providing direct patient care, numbers of years practicing within disease area and numbers of patients treated within a typical monthly period [7, 8]. For the remaining studies and appraisals, experts were largely described as per their clinical discipline, without any quantification of length of time within the area or length of time practicing.

Use of existing protocols or frameworks

All identified studies within the broader literature, except that by Willigers et al. [23], used SHELF [15] as the base framework for the design of the elicitations whereas two out of four [28, 29] of the NICE appraisals used the MRC protocol [13], with the two remaining appraisals not referencing specific frameworks. All cases where an existing elicitation protocol or framework was cited, acknowledged the necessity for significant modifications to the original framework, for instance modifications to enable the elicitation of survival at multiple timepoints [8] and the adaptation into what appeared to be a remote format where experts could work through the questions in their own time [21].

Setting of the elicitation

None of the studies identified from the broader literature appeared to conduct the elicitation in a face-to-face setting, though Klijn et al. and Konidaris et al. did not explicitly report the format of the elicitation [26, 27]. Both Federico Paly et al. and Willigers et al., appeared to have conducted the elicitations remotely, using a questionnaire format, as opposed to a structured discussion [21, 23]. Ayers et al. and Cope et al., again used similar approaches as each other and conducted the elicitations virtually [7, 8]. Three of the four NICE appraisals [28,29,30] stated that the elicitation took place as part of advisory board meetings and TA954 reported that this was conducted face-to-face. In TA975, the meeting was held virtually but it is unclear whether the meeting was specifically for the elicitation relating to survival outcomes, or whether other issues relating to the submission were also discussed [31].

Provision of an evidence dossier

A key element of structured expert elicitation exercises, as described in multiple existing elicitation protocols, is the construction and provision of an evidence dossier. The evidence dossier helps to summarise all relevant data for participating experts and thus serves to minimise availability bias [13, 15, 18]. Four out of six of the studies in the broader literature recorded that an evidence dossier was provided to the experts prior to the elicitation exercise, and one of these studies, by Federico Paly et al., included the dossier within the supplementary material of the publication [21]. The dossiers typically included summaries of relevant trials and a summary of the purpose of the elicitation. In the evidence dossier compiled by Willigers et al., it was stated that potential extrapolations of the survival data were included, the authors however acknowledged this could have biased experts when making their initial judgements [23].

All the NICE appraisals appeared to provide “pre-read” materials to experts ahead of the elicitations however the content of the dossiers appeared to vary considerably. In TA917 and TA967, details of the dossier contents were not provided, but in TA917 it was stated that experts did review the dossier in order to ensure no relevant material was omitted [28, 30]. Both TA954 and TA975 included general descriptions of the dossier contents, but in TA954 it was highlighted that “modelling approaches” were also included. It was not clear whether this related to the extrapolation of survival data or other modelling assumptions [29, 31].

The majority of the studies in the broader literature and the NICE appraisals did not describe how the evidence dossier content was sourced. Willigers et al. noted that a systematic literature review was not conducted when sourcing information for the dossier, which posed a potential limitation, by contrast, in TA967 a systematic literature review was used to populate the dossier [23, 30].

Definition of quantities of interest

During the preparation of the elicitation, the quantity of interest (QoI) must be defined clearly such that experts are making judgements of the same quantity.

In all studies identified from the broader literature, survival quantities at multiple landmark timepoints were elicited, and in some cases these quantities were elicited alongside the mean lifetime survival. This was mirrored in all but one [30], of the NICE appraisals. Typically, the chosen timepoints reflected time periods in keeping with the standard progression of the condition of interest, though these time points did largely tend towards more rounded landmarks such as 10 or 20 years with no justification of their choice. Survival appeared to be largely described as a proportion, but in TA975, experts were asked to express the survival as the number of patients who would still be alive out of an initial number of patients at a given time point [31].

Ayers et al., in addition to the survival proportion at three time points, asked experts to provide the time at which they believed the survival to be 0%. This value served as an anchor to the experts and helped the experts “consider the potential shape of long-term survival” [7].

Most studies did not aim to elicit conditional survival outcomes. However, Ayers et al. and Willigers et al. defined the quantities of interest such that this explicit relationship between multiple time points was considered whilst experts made their judgements [7, 23]. Ayers et al. asked experts, to consider the survival at subsequent time points conditional on their judgements at earlier time points. Whereas Willigers et al. first asked for the non-conditional expert judgement of survival at 10 years and then for the survival proportion at 20 years, based on two pre-chosen conditions: survival at 10 years was 40% and survival at 10 years was 70%. Explicit consideration of conditional survival did not appear to be accounted for in the NICE appraisals.

Provision of statistical training

The elicitation conducted by Willigers et al. reported statistical training of experts, prior to the making of their judgements [23]. The training encompassed details of how to complete the survey, a summary of common biases and heuristics [33] and descriptions of percentiles and their interpretation. Ayers et al. and Cope et al. appeared to also provide statistical training, though the training by Cope et al. appeared to be in a self-directed format [7, 8]. Out of the four NICE appraisals, only TA967 stated any provision of training [30]. TA967 used the Structured Expert Elicitation Resources (STEER) materials [34], which closely align with the MRC protocol [13], and provided a training question to help familiarise experts with the interface which facilitates the input of their judgements.

The experts in the study by Willigers et al. appeared to make their judgements remotely, however the training was conducted via a one-hour virtual session with experts [23]. In TA967, training materials were provided to experts and they were encouraged to contact the elicitation team if they had queries, it was not stated whether any experts did reach out regarding the content in the training [30]. All other studies and appraisals did not mention the provision of statistical training to experts.

Elicitation methodology and conduct

Following the provision of training or review of the evidence dossier, experts are required to make their individual judgements for each quantity of interest. In the broader literature, both Ayers et al. and Cope et al. asked experts to provide the upper and lower plausible limits, alongside a most likely value [7, 8]. Federico Paly et al., Klijn et al. and Konidaris et al. all asked for upper and lower limits with a central or mean value [21, 26, 27]. Willigers et al. instead asked experts to provide judgements of the 10th and 90th percentiles, along with the median [23]. All of the studies identified in the broader literature therefore appeared to use a variable interval method, as opposed to a fixed interval method where they would instead make judgements on the probability of the true value falling within pre-defined ranges.

In TA954, it was not clear what method was used when experts were making their individual judgements and how expert uncertainty was captured quantitatively [29]. In TA967 the “chip-and-bin” method was utilised, which was implemented via the STEER materials, however it was not clear whether the bins were predefined or defined by the experts themselves [30, 34]. In TA917 and TA975, experts, as in the broader literature studies, were asked for upper and lower estimates of the quantities of interest, along with a most likely value [28, 31].

All but one of the cases discussed within this review had more than one participating expert, therefore aggregation of individual judgements would have been required in the remaining studies or appraisals. How this aggregation was performed was not reported in two of the studies from the broader literature [21, 27]. Of the appraisals, only TA967, which was based on the MRC protocol, described the mathematical linear pooling of the individual expert judgements via the SHELF fitdist function [30]. This was conducted during the advisory board meeting and was discussed by experts during the consensus session.

Both Ayers et al. and Cope et al. explicitly recorded expert rationale during the elicitation [7, 8]. Ayers et al. asked experts to comment on what sources of information they primarily used when making their individual judgements and then also recorded any points in discussion during the consensus meeting where experts disagreed. Experts’ rationale and reasoning were also recorded by Cope et al., again at the stage of the consensus meeting. It did not appear that any of the other studies identified within the broader literature recorded qualitative rationale, or this was not presented within the summary of the elicitation.

In TA917, discussion amongst experts was evident, and it appeared that this took place after the meeting where experts initially provided their judgements [28]. In TA967, as part of the STEER materials, experts were required to provide their judgement rationales via a free text box, these were then collected and discussed at the subsequent advisory board meeting [30]. Within TA967 it was highlighted that the qualitative rationale from experts was useful in providing meaningful insights to the inter-expert variability. In both TA917 and TA967, it appears that the expert rationales were summarised in more detail and available within the submission appendices, but these were not publicly available and so could not be assessed as part of this review. In TA975, again it appeared that opinions and discussions of experts were recorded and available within the appendices, however it was not clear whether this specifically related to the elicitation of the survival outcomes or other issues discussed within the meeting [31].

Despite the inherent relationship between the survival function and the hazard function, none of the studies in the broader literature or the identified NICE appraisals appeared to discuss the hazard trend directly, either as rationale for experts, or as a source of validation as recommended in NICE TSD 26.

Use of elicited quantities

Despite the primary outcome of a structured expert elicitation being to provide a probability distribution summarising expert uncertainty, only three out of the six studies in the broader literature appeared to utilise the resulting expert distributions [7, 8, 23]. In the studies by Ayers et al. and Cope et al. the aggregated probability distribution corresponded to that of the “rational impartial observer” as recommended by SHELF [7, 8, 15]. The aggregated distributions were subsequently used to constrain the fitting of the survival models. Willigers et al. similarly used the elicited distributions within a Bayesian survival analysis setting [23]. The three remaining studies appeared to use the expert judgements for external validation, and helped refine the model choice by excluding any model with extrapolated survival outside of the identified plausible range [21, 26, 27]. This was further supported by the lack of reporting of aggregation methodology for these three studies.

In the NICE appraisals, there were variable uses of the expert-derived distributions or ranges. In TA917, experts provided their individual judgements of the quantities of interest and were also asked to rank different extrapolations of survival in terms of their plausibility, whilst excluding any that did not appear plausible as per the experts’ original judgements [28]. In TA954, the most-likely values, provided by the experts were used to assess validity of the extrapolated curves, but the expert uncertainty did not appear to have been considered during selection of the models [29]. In TA967, experts provided individual judgements which were subsequently mathematically aggregated [30]. Within the appraisal a single, “experts’ preferred distribution” is then referenced, however it is unclear how the distribution from the elicitation contributed to the choice of the preferred model. Finally, in TA975 experts were asked to use their own individual judgements to determine specific extrapolations which were not clinically plausible (due to them falling outside of the experts’ upper and lower range) and their overall preferred extrapolation with regards to clinical plausibility [31].

link